Jud Simons knew of her fate long before the Nazis took her.

It had barely been a decade since she was crowned Olympic champion in the very city, Amsterdam, that was now shackled and chained amidst Adolf Hitler’s cross-continent destruction. Since the day that Simons collected her gold medal with the Dutch Gymnastics team, she had devoted herself, alongside her husband, to caring for 80 children at their orphanage just south of the capital in Utrecht.

The horror stories of the Nazi’s ‘Final Solution’ had long amplified from perverse rumour to emetic fact, but Simons did not abandon those who depended on her, even in the wake of the unimaginable fate that loomed. The then 38-year-old was deported to Sobibor extermination camp with her family, never to return to the orphanage she stood by when so many would have fled.

Simons was gassed. Her husband was gassed. Her five-year-old daughter was gassed. Her three-year-old son was gassed.

Tokyo 2020’s cancellation

Today, 77 years later, the technicolour rings of the Olympic movement were due to flutter over Tokyo as a triumphant opening to the 2020 Summer Games. They do not. Instead, 2020 marks the first time since the epoch of Nazi devastation that sport’s quadrennial celebration has been kneecapped by tragic circumstances.

It’s a detail of great poignancy for occurring in the year of the 75th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation – and if the two cancellations share anything in common, it’s in the viral nature of its cause. One can’t help but feel, after all, that the racism and anti-Semitism of both the 20th Century and contemporary times are as manifest and pandemic as the biologic threat we face today.

The tragedy, however, is in the fact that only one is man-made.

‘A nail in the coffin’

It’s estimated that over 10 million people perished in the Holocaust and as Agnes Grunwald-Spier’s wonderful ‘Who Betrayed the Jews?’ reveals, there were many Olympians amongst them. The quote ‘one death is a tragedy; one million is a statistic’, which is often attributed to Josef Stalin, is perhaps an ill-fitting rhetoric to how many have come to view the Nazi horrors in the decades since.

When the body counts of the Holocaust are outlined, it tends not to affect people as much as it does when individuals and their stories are spelled out with poignant details. It’s a phenomenon that Grunwald-Spier – a Holocaust survivor herself – describes as ‘Anne Frank syndrome’, the idea that people can relate to one young girl, such as Frank, better than the incomprehensible sum of six million Jews.

“I always give a powerpoint presentation instead of just standing there talking because I like to show people the faces of the people I’m talking about,” she explained to me on the phone. “But there’s also the other side to it: every individual story that’s recorded is a nail in the coffin of the Holocaust deniers. I always tell people: ‘you must tell your story’.”

It is, therefore, with a handful of nails that Grunwald-Spier emerges from her research into the Olympians of the Holocaust. The resonance that each story carries into the present helps to hold down the coffin lid tighter, snowballing in importance in a world where so many fallacies and mistruths are pedalled about the Nazi regime and anti-Semitism.

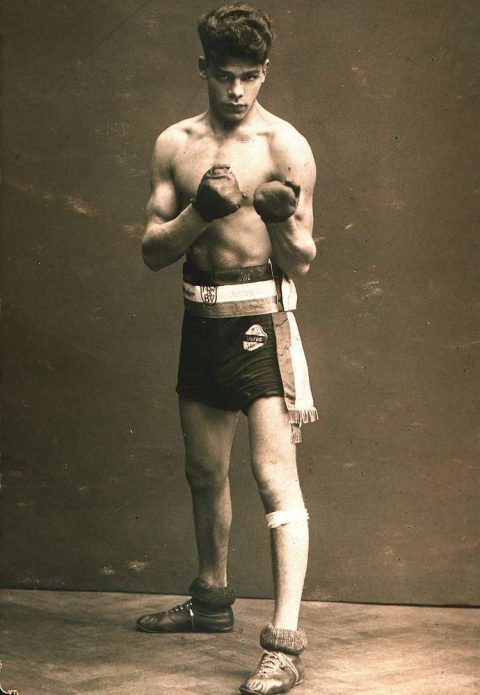

Johann ‘Rukeli’ Trollmann

The bubbling pot of racism at the heart of the Holocaust is wholly apparent in the story of German boxing champion Johann ‘Rukeli’ Trollmann. The revered fighter was shockingly denied the chance to represent his country at the 1928 Olympics for his ‘yellow, non-German style’ and was later panned in the fascist media for being ‘the gypsy in the ring’.

We now live in a world where the ‘Gypsy King’ – Tyson Fury – is a heavyweight champion, but Trollmann was marginalised for his Sinti heritage and unlawfully stripped of his German title in 1933 for ‘dancing like a gypsy’. But it was with untold defiance that his final professional bout saw him dye his hair blonde and ‘whiten’ himself with flour to make a mockery of the Nazi’s Aryan iconolatry.

Trollmann was eventually sent to the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg where, despite being a shadow of his former self, he was forced to fight high-ranking SS officer Emil Cornelius. Astonishingly, Trollmann defied all the odds to win the contest, only to be murdered in a cowardly act of revenge by Cornelius during forced labour in front of his fellow prisoners.

It wasn’t until 70 years later that Trollmann was rightfully installed as a Germany light-heavyweight champion with his only surviving relatives collecting the belt.

Attila Petschauer

The atmosphere of hate during Nazi rule in Europe was also detectable in the betrayals and disloyalties it propagated. Attila Petschauer was crowned an Olympic fencing champion at Los Angeles 1932, an improvement upon his silver in Amsterdam, but would ultimately fall victim to the very nation for which he had become such a decorated sportsperson.

The sabre competitor survived much of the early war years through a ‘document of exemption’, due to his sporting success, though he was sent to Davidovka concentration camp in 1943 after leaving his ID papers at home before a routine check. Most tragically of all, however, is the fact one of the men responsible – Kalman Cseh – knew him personally having been on the Hungarian delegation for the 1928 Games.

Through the harrowing testament of fellow Olympic champion Károly Kárpáti, we know that Pestchauer was murdered during a digging exercise in sub-zero temperatures. The fencer was told to undress, climb a tree and crow like a cockerel, only to be sprayed with water that froze on his body until he fell from the vegetation and died in the barracks hours later.

His compatriot Kárpáti survived until the Soviet liberation and his telling of that most traumatic of memories provides us with another nail, wrought with bravery. The origin of Petschauer’s abduction is one that stuck with Grunwald-Spier who, herself a Hungarian of birth, notes how incidents of this nature led to her father Philipp losing faith in his countrymen.

“My father was a forced labourer,” Grunwald-Spier explained to me. “They were in the hands of Hungarian soldiers and they were treated incredibly badly. My father was very lucky to come back and he was very bitter about his experiences. He wouldn’t have any more children after the war.”

Lenke Ziszovits-Popper

Her father, who sadly committed suicide in 1955, was born in the Romanian city of Oradea, though it fell inside Hungarian borders at the time. It is the same settlement in which tennis champion Lenke Ziszovits-Popper, born a year before Philipp, called her home after moving at age 14 and it’s thanks to the brilliant work of those at Asociatia Tikvah that her own story can be told.

Ziszovits-Popper was a remarkable athlete on the court, winning the Romanian National Ladies Championship in 1930 and 1938 as well as the Ladies Singles Championship at Berlin’s Jewish Bar Kochba Club in the same year of Hitler’s Olympics. However, her tennis career was ended prematurely just a few years later when sporting structures for Jewish people were dissolved.

Her husband, Erno, was abducted into forced labour in 1943 while Ziszovits-Popper was pregnant with their child, Zsuzsi, who was born the following year. Mother and daughter were moved into the Oradea ghetto, before being transported to Auschwitz by cattle truck from the very Rhedey Park in which she had played tennis as a youngster. Neither Lenke or her daughter survived.

Erno later returned from the labour camp as part of a group of prisoners tasked with gutting the empty ghetto. He found there the carry-cot of his baby daughter and one of his wife’s tennis bracelets.

Grunwald-Spier and Tikvah play an invaluable role in recounting these athletes’ stories, of which we have named but a few, by exposing how – just like German ‘Iron Cross’ winners of the First World War – prior achievements were futile against the Nazi snow-plough of intolerance. Their discrimination was so frightening for being so indiscriminate within it.

The 1936 Olympics

There is also a terrifying nature to the Nazi’s self-awareness of their racism. The Third Reich’s ties to the Olympics can, of course, be traced back to the 1936 games to which they played host. It seems unimaginable today that the face of all that’s good in sport would be surrendered to a regime that was forced to scramble to remove anti-Semitic propaganda before staging it.

They knew they would be globally condemned for their policies, so they hid it from the world and then brought it to their doorstep three years later. The triumphs of Jesse Owens – who won four gold medals in Berlin – are well-documented that summer, but it’s in these exceptional circumstances that the voice of someone younger and more innocent often carries the most weight.

Dorothy Tyler-Odam was merely 16 years old when she won a silver medal in the high jump in Berlin, but her recollections of the experience arguably endure as much as her achievement. As outlined in ‘Who Betrayed the Jews?’, she described Hitler as a ‘small man in a big suit’ and mused that their German chaperones had been deployed to spy on them.

When the competition was held on warm summer days, she recalled how only the German girls were given water and they ‘got nothing’. That, and her haunting post script that read: “I received a smuggled letter from an inmate of a concentration camp telling me of the atrocities and asking me to take it back to England. I showed it to my chaperone but never saw it again.

“I wonder what happened to that poor soul?”

Something about the baseness of Nazi hatred being injected into the smallest of details makes the skin crawl with its thoroughness.

Eternal memorials

The stories of these Olympians and sportspeople from Simons to Trollmann, just like everybody who died in the Holocaust, are memorials. They are reminders that as long as there is bigotry, racism, prejudice, intolerance and hate in the world that everybody is responsible to ensure there will never be another Holocaust. But most importantly of all, they are nails.

Like Grunwald-Spier, we must hold on to as many of those nails in order to ensure that the horrors of both the past and present remain caged, never to return and never to be forgotten. For even in man’s inhumanity to man, there is ‘humanity’ to be found.

A special thank you to Agnes Grunwald-Spier for her invaluable research, cooperation and input as part of this article. Any articulation of the importance of her work would, frankly, be futile. Aside from her cited release ‘Who Betrayed The Jews?‘, you can also read her other works: ‘The Other Schindlers‘ and ‘Women’s Experiences in the Holocaust‘.

This article was first published by Give Me Sport on 24 July 2020. Grateful thanks to Kobe for his hard work and enthusiasm.